- Home

- Lynn Povich

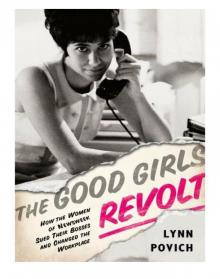

The Good Girls Revolt Page 9

The Good Girls Revolt Read online

Page 9

There was a discussion about whether we should work through the Newspaper Guild, which represented Newsweek employees in contract negotiations with management. But the Guild, dominated by blue-collar men, had not been in the forefront of civil rights, let alone women’s rights, so we nixed that. Then someone raised the possibility of sending a delegation to visit Kay Graham, thinking that as a woman she might be sympathetic. Others thought we should first go to the editors and give them one more chance. “Even I found it hard to stick it to them,” remembered Judy Gingold. “I respected a lot of those people. Oz had three daughters and he was so proud that one of them had gotten eight hundred on her college boards. But all I could think of was, a lot of good that will do her! It was very difficult sustaining the belief that I was right, because how could I be right and Oz Elliott wrong?” Fay was reluctant to file any legal action. She kept asking, “Why can’t we just talk to them?” and we kept saying, “It won’t work, they won’t listen.”

There was one obvious reason it wouldn’t work. Six months before we started to organize, ten of the senior writers on the magazine organized what became known as “the Colonels’ Revolt.” They were bitching about the usual issues of news-magazine writers: their ideas weren’t listened to and they wanted a more personal voice in their stories. The writers held a meeting and drew up a list of “nonnegotiable demands,” which is what all movements presented to the power structure in those days. They drew a map of the Wallendatorium on a chalkboard with arrows pointing to each office—wanting them to think they were plotting a sit-in—and purposely left it there, hoping it would be found. It was, and the Wallendas immediately met with the Colonels, not as a group but individually. “Every Wallenda was assigned to someone and I got Oz,” recalled Peter Goldman. “They picked us off one by one. Some people got raises, some promotions, and we all got to recite our demands. But essentially nothing happened.”

If the editors co-opted their most valued employees, we thought, why would they listen to their lowliest staffers? That’s why many of us were willing to go to court. But Eleanor still had to convince us. We began meeting with Eleanor in the evenings, in what became a six-week boot camp in power politics. “It wasn’t a case of me convincing you,” she later said. “We met so many times precisely because the women had to convince themselves. You knew you were on the frontier and you all had to discuss what was happening. But I had to keep telling you the truth. You’re the crème de la crème—what the hell are you afraid of? You’re smarter than these guys, they’re taking advantage of you, and when the court sees your credentials, their eyes will pop out.”

Sitting in her apartment at 245 West 104th Street, Eleanor would cut and devour slices of raw onion—one of her pregnancy cravings—as she harangued us to screw up our courage. When we explained the researcher job and how all the decisions were made by men, she was shocked. “This is one of the great dictatorships in the history of magazines!” she exclaimed. She was also surprised by our naïveté. “You gotta take off your white gloves, ladies, you gotta take off your white gloves,” she would say. At one point, fed up with us all, she yelled, “You God damn middle-class women—you think you can just go to Daddy and ask for what you want?”

We all were terrified of Eleanor but there was a method to her madness. She had to shape us into a tough, solid group. “Only one or two plaintiffs would have been very vulnerable at that early stage in a sex discrimination investigation,” she later explained. “They could lose their jobs, even though there is a separate cause of action against retaliation. Or if they didn’t lose their jobs, they’re the ones who would be fingered, and everyone else would get the benefit of what a couple of people did.” Even though she thought we had a strong case, Eleanor was worried about the fight. “If enough women would come forward, then there would be protection against you all becoming fodder,” she recalled. “I didn’t know if you would be fodder. I realized Newsweek was a liberal publication, so to speak. But when you go up against management—you go up against management.”

CHAPTER 6

Round One

AS HARD AS WE TRIED to keep our plans secret, they began to leak out. The Friday before we were to announce our lawsuit, Rod Gander invited Lala Coleman to lunch. They were friends—she was dating one of his reporters at the time—and the two would often go out for a few mint-flavored grasshoppers. At lunch, Rod asked her what was going on with the women. Suppressing her surprise, Lala coolly replied, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” “You can’t even look me in the eye when you say that,” he immediately shot back.

The next evening, after closing the Foreign section, Fay Willey was returning home with her groceries when the phone started ringing. She picked it up and was stunned to hear Oz Elliott on the other end. It turned out that one of the researchers in the Business section, who had been checking changes with writer Rich Thomas Friday night, had let it slip that the women were going to put out some sort of press release Sunday evening. Rich called Oz on Saturday and tipped him off. That evening, Oz told me years later, “I called Fay and said that I heard something big was going to happen with the women at Newsweek and that it would surface the following week.” Oz pressed Fay to tell him what it was, saying the women should first come to management with their grievances. Fay was shaking. She greatly admired and respected Oz but she was scared of giving anything away. “In a very cold voice,” Oz recalled, “Fay said she couldn’t say anything, that the train was too far down the track.” He made several attempts to convince her to tell him, appealing to her as a longtime, senior employee and a levelheaded one. Bravely holding her ground, she said simply that she would pass his message on to the women. “When I was told that Fay was involved, I felt it gave the whole thing gravitas,” Oz told me. “She was no miniskirted recent grad from Radcliffe. She was part of the old guard.”

Clearly worried about what was going to happen, Oz called Fay again Sunday morning, this time with a more serious concern. He reminded her that the press was under attack from the government and warned her that whatever the women were planning might have political repercussions for the magazine. In late 1969, the Nixon administration had begun its war on the “Eastern establishment elitist press.” At one point Vice President Spiro Agnew declared that the Washington Post was part of “a trend toward monopolization of the great public information vehicles,” saying that the Post and Newsweek, along with the Post Company’s radio and television stations, “hearken to the same master.” Oz appealed to Fay not to get the government involved and offered to meet with the women anytime. Fay again held her ground and promised to relay his concerns to the women.

There was one person we felt we should call: Helen Dudar. Pat Lynden offered to call her at home after we announced our suit. “That was incredibly helpful,” recalled Peter Goldman, Helen’s husband, “because Pat assured Helen that the suit wasn’t personal—it was about going outside for someone to write the cover.” Helen was part of the generation of women who had to make it on their own against great odds and she succeeded in every respect. “I idolized her,” wrote Nora Ephron in a foreword to Helen’s collected works, The Attentive Eye: Selected Journalism, edited by Peter. Nora, who worked with Helen at the New York Post, said, “Helen could do anything. She could write a lyrical feature piece, she could write hard news, and she was—in a city room full of world-class rewrite men—the greatest rewrite man of all.”

Like many professional women of her generation, Helen hadn’t embraced the women’s liberation movement; she took the Newsweek assignment because she thought it was interesting. “She was in pre-feminist mode then,” said Peter of his wife, who died in 2002. “I don’t think she thought about the political context of the cover story. If I had been smarter I would have said this assignment has hair on it. But I wasn’t smart then. You all woke me up and the assignment woke Helen up.” For Helen, reporting on the new feminism was a voyage of self-discovery. “It was her consciousness-heightening period but I don’t th

ink she connected it with the Newsweek system,” said Peter. “We used to talk about how one of the fringe benefits of Newsweek was that I had women pals for the first time in my adult life. But I wasn’t bringing home that it was a caste system and that it wasn’t fair.”

When the couple discussed the assignment at home, “Helen was just communicating bits to me because she was assimilating it in bits,” Peter recalled, “not in the sense of becoming an activist. She was like me on the civil rights movement—we were chroniclers. When Pat Lynden called, it was the first bell, an ‘Oh my God’ moment for both of us. Why didn’t we get it? How could we—particularly me—not have figured this out? When the story of the legal action unfolded, it was like a revelatory experience.”

The final irony of hiring Helen to write the Newsweek cover is that she ended up being a convert to the women’s cause. Although Newsweek’s contents page, written by the editors, introduced the “Women in Revolt” cover in ominous tones, “A new specter is haunting America—the specter of militant feminism,” Helen’s report on the new feminism ended with the following thoughts:I have spent years rejecting feminists without bothering to look too closely at their charges.... It has always been easy to dismiss substance out of dislike for style. About the time I came to this project, I had heard just enough to peel away the hostility, leaving me in a state of ambivalence.... Superiority is precisely what I had felt and enjoyed, and it was going to be hard to give it up. That was an important discovery.... Women’s lib questions everything; and while intellectually I approve of that, emotionally I am unstrung by a lot of it. Never mind. The ambivalence is gone; the distance is gone. What is left is a sense of pride and kinship with all those women who have been asking all the hard questions. I thank them and so, I think, will a lot of other women.

The Sunday evening before we filed the suit, when we gathered at Holly Camp’s apartment to work out the final details, Fay told us about Oz’s calling her at home. She relayed how he reminded her of the Nixon administration’s hostility toward the press and asked for another chance. Fay felt that Oz had made a good case, and once again she pleaded with us to go to the editors first with our grievances. We were shocked that Oz had found out about our plans but we were also impressed—and grateful—that Fay had fended off the boss and kept our secret. Still, we were convinced that filing a legal action was our best chance for change and protection. Our final act that evening was to sign the EEOC complaint, which had to be in the mail before midnight. As we solemnly lined up, I felt the thrill and the terror of what we were about to do. There was no turning back. One by one, we recorded our names on the historic document.

The next morning, thirty of us arrived at the ACLU an hour before the 10 A.M. press conference. We nervously started setting up the wooden chairs in the makeshift boardroom and then we waited—and waited. By 9:30, no one from the press corps had arrived. We started to panic. Our entire strategy hung on getting publicity. What if no one came? Finally some cameramen and reporters started filing in, including Susan Brownmiller, who had been invited by her former Newsweek colleagues to bear witness. When Gabe Pressman, the popular NBC reporter arrived, recalled Margaret Montagno, “I thought, ‘Aha—this really is an event!’”

After the press conference, most of us in the back of the book and Business went back to the office. Judy, Margaret, and Lucy went to lunch at a small restaurant near the ACLU to celebrate. As they toasted the women’s movement and each other, Judy kept yelling, “We did it, we did it!” The next morning, the women met again at the Palm Court in the Plaza Hotel with Pat and, over croissants and champagne, they read the newspaper accounts of the press conference out loud. “I was annoyed that I was called a respectable young woman,” remembered Pat, “and amused that the Daily News called us ‘Newshens’!”

When Lucy and Pat went into the office later that Tuesday morning, they ran into Oz on the eleventh floor. “How do you feel about what happened?” Pat asked him. Oz immediately invited them into his office, where they talked for forty-five minutes. “First Oz said how hurt he was,” recalled Pat. “Then he asked, ‘Why didn’t you come to me?’ Lucy said we had—we came many times in many ways. He listened to us but didn’t concede anything.” Lucy was insulted because Oz said, “I can understand you, Pat, but Lucy—you are such a nice girl.”

Kermit Lansner, the magazine’s editor, seemed to dismiss the whole thing. Whenever there was ever a ripple in the pond of tranquility at Newsweek, Kermit would typically say, “Madness . . . It’s all mad.” We thought managing editor Lester Bernstein felt betrayed, furious that these lowly employees had soiled his magazine’s reputation. One editor, we were told, simply said, “Let’s just fire them all.” Only Oz took the lawsuit seriously. As the father of three girls, he was particularly chastened by the charges of discrimination against women. “My consciousness at the time was zero,” he admitted to me before he died in 2008. “Here we were busily carving out a new spot as a liberal magazine and right under our own noses was this oppressive regime—and no one had a second thought! It was pretty clear to me on that Monday that the women were right.”

That was one of the chilling contradictions of the culture: advocating civil rights for all while tolerating—or overlooking—the subjugation of women. “My theory is that we were all blind to the fact that we were sitting on top of a caste system,” said Peter Goldman. “It was this ’50s mentality and the fact that Newsweek was copying Time. It seemed natural that women were in servile roles and as you keep hiring, the overcaste and the undercaste become self-sustaining. By the time I got there in 1962, the men just accepted this as the way things were and I think the women accepted it the same way.”

But after that Monday in March, it was a whole new story. Some of the correspondents in the field sent congratulatory cables. “The all male San Francisco bureau (and chief stringer Karen McDonald) say right on sisters,” read a telex from bureau chief Jerry Lubenow and reporters Bill Cook and Min Yee. The female correspondents immediately signaled their support, especially Liz Peer in the Washington bureau. “Liz was a cheerleader,” recalled Mimi McLoughlin, the Religion researcher. “She thought of herself as a woman who had succeeded on her own and somewhat distanced herself from it. But she’d always say, ‘You guys are great.’”

Most of the writers supported their female colleagues. “My attitude was ‘Go for it,’” recalled Peter Goldman. “We were in a ‘movement’ frame of mind and as soon as the women lit the match, it was obvious. I also thought doing it through a lawsuit was the right way. I had been covering the civil rights movement and Vietnam and I thought, ‘Okay, here’s one more revolution—this is inevitable and it had to happen.’” Harry Waters remembered viewing the women’s plight less as a gender issue than as one of injustice. “I was a young guy who started as a fact checker,” he said, “but I always knew—and was told—that I would get a shot at reporting, writing, and editing. For a young, ambitious, talented woman, that elevator was out of order.”

Not everyone was espousing a new order, however. As in many organizations, it was middle management that was most resistant to change—in our case, some of the senior editors who ran the six editorial sections of the magazine. With the exception of my boss, Shew Hagerty, and Ed Diamond, none of the other senior editors had promoted a researcher to writer, nor had they hired a woman as a writer. In her memoir, Susan Brownmiller described being called into Newsweek several weeks after the press conference to meet with the Wallendas. They inquired whether she would be interested in coming back to the magazine as a writer, but she declined. “My idea of a cold-sweat nightmare was eighty-five lines for Nation on a Friday night—it still is,” she wrote. Afterward, she was pulled aside by Lester Bernstein, her former boss when he was the senior editor of Nation. “When you worked here, Susan, did you have ambition?” he asked. As she noted in her book, “For two years not a week had gone by without my asking if I could ‘do more.’ He hadn’t noticed.”

After we announced our l

awsuit, Oz sent a memo to the women Monday afternoon. Saying that he was “naturally dismayed at your evident unhappiness,” he called for a meeting the next day at Top of the Week, the elegant penthouse of the Newsweek building where visiting dignitaries were entertained. Designed by I. M. Pei, Top of the Week had a sumptuous beige salon with luxurious couches and chairs, large and small dining rooms, and a kitchen. Before our Tuesday meeting with Oz, Eleanor had instructed us not to say a word until she got there, because she didn’t want us to incriminate ourselves.

Oz had arranged rows of folding chairs for the women facing one of the soft suede couches where he had placed himself and Kermit. “Big mistake,” Oz later told me. “The sofa was about a foot and a half lower than the chairs and now Kermit and I are looking up at forty-seven women—our knees under our chins. I said, ‘I’d like to say a few words before we start,’ and this cold voice from the back of the room says, ‘Sorry, Oz, we’re not going to do anything until our lawyer gets here.’ Oops, I thought, this is going to be a heavy session.” We sat there awkwardly for a few minutes until Eleanor finally arrived. “In comes this very angry, very articulate, very smart, very pregnant, very black Eleanor Holmes Norton,” Oz said. “I welcomed her and said, ‘Please take a seat. I just want to say a few words to the women before we get started,’ and she said, ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Elliott, but this is our meeting—we will do the talking.’ She had me splattered on the wall. Boy, she was tough. How much of that explosive nature was affected and how much was just sheer anger I don’t know. I think a lot of it was playacting, but she was sharp.”

The Good Girls Revolt

The Good Girls Revolt