- Home

- Lynn Povich

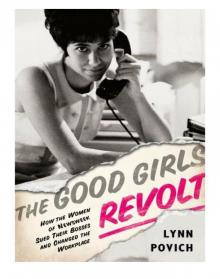

The Good Girls Revolt Page 11

The Good Girls Revolt Read online

Page 11

Some men questioned whether forcing management to promote women from within was a good idea. One was Ray Sokolov, a Harvard Crimson alum who was writing in the Arts sections. “The researchers were problematic as a category,” he recalled. “Almost none of them had a background in journalism.” It is curious that none of the Newsweek editors had hired—or considered hiring—experienced women journalists from other publications. “There really was sexism at work in some way that made no sense,” said Ray. “They could have found six women reporters in any of the daily journalism publications and not have had to wait for their potentially capable researchers to make it as writers.”

In the mid-1960s, there were a few women writing at Time, where Newsweek editors often looked for talent. Some magazines, such as BusinessWeek, hired women as writers right out of college and all the major newspapers carried female bylines. When Katharine Graham suggested in the early 1960s that former New York Times art critic Aline Saarinen be hired as an editor at Newsweek, the editors dismissed her out of hand, she wrote, “condescendingly explaining that it would be out of the question to have a woman. Their arguments were that the closing nights were too late, the end-of the-week pressure too great, the physical demands of the job too tough. I am embarrassed to admit that I simply accepted their line of reasoning passively.”

After the agreement, however, the editors began pursuing female writers from outside the magazine as fast as they were scuttling the tryouts of women inside. The first woman they hired was Barbara Bright, who had been a stringer for Newsweek in Germany. She had returned to the United States and became a writer in Foreign. Then they approached Susan Braudy, an experienced freelancer for the New York Times Magazine, who went on to become a writer and editor at Ms. magazine and the author of several best-selling books. I had met Susan when we were reporting on the first Congress to Unite Women in August 1969, and we had become good friends. In December 1969, Susan wrote a freelance piece for Playboy on women’s lib, but it never ran—Hugh Hefner spiked it. Hef’s memo as to why he didn’t like the piece was later leaked to the press by a Playboy secretary (who was promptly fired) and it became a cause célèbre. “What I want,” Hef said, “is a devastating piece that takes militants apart.... What I’m interested in is the highly irrational, kooky trend that feminism has taken. These chicks are our natural enemy.... It is time to do battle with them.... All of the most basic premises of the extreme form of the new feminism [are] unalterably opposed to the romantic boy-girl society that Playboy promotes.”

Joel Blocker, by now a senior editor in the back of the book, first contacted Susan because, he told her, Newsweek wanted to do a “sympathetic” story on the contretemps, which ran in May 1970 (her own piece eventually ran in Glamour in May 1971). The following year, he offered her a tryout. Susan wrote in the back-of-the-book sections but struggled with writing Newsweek style. She and I talked often about this, but I was having my own problems with Blocker and wasn’t much help. After a year, she left in the summer of 1972. “They wouldn’t let me do my own reporting,” she recalled, “and I didn’t understand the condensation, the formulaic writing, and the kickers at Newsweek. But I learned a lot. I learned to write when I didn’t like what I was writing.”

Diane Zimmerman, a star reporter in the back of the book, had been writing occasional stories for the Medicine section and others. After we filed the complaint, she asked her editor, Ed Diamond, for a tryout. “With all his peculiarities, Ed was very fair and pushed for me,” she remembered. “The Wallendas said they would do it but that they weren’t ready yet. I tried to get a tryout for at least eight or nine months and I couldn’t get one. The Wallendas didn’t approve it.” Diane left in 1971, when Shew Hagerty moved to the New York Daily News and hired her there.

There were also pockets of resistance by some writers and reporters. In February 1971, I received the following story suggestion via telex from Jim Jones, the crusty Detroit bureau chief: “A group of women’s lib sows here, who are members of the Detroit Press Club, are demanding that they be admitted to the club’s annual ‘Stag Steakout,’ a gridiron-type affair where the insults and language are a deep blue.... Now it appears the club’s board of governors may bend and admit the broads at the do in March (partly this is because a governor or two has a mistress or two among the libbies and are afraid that they’ll get cancelled out if they don’t vote favorably). This is a teapot tempest, but I’m advised the NY Times is working up a story involving the hassle, and maybe you’d want to take the edge off that.”

Infuriated, I telexed Jones back ordering a fifty-liner, with a zinger at the end. “Allowing for your clearly sexist item, appreciate as objective an account as possible.” For that, I was called into Rod Gander’s office and, with Jones on the phone, told we had to settle our differences amicably. We grudgingly did but the story never ran.

By March 1971, the women’s panel realized that management wasn’t living up to even the spirit—much less the letter—of the agreement in recruiting women writers, inside or out. Once again, we contacted Mel Wulf at the ACLU, who wrote to the editors requesting a meeting “since there are failures involving the pace of implementation” of the agreement. He also noted that “it is unethical and a breach of the agreement to set up your obligation to seek out blacks as in some way mitigating your obligation to rectify the imbalances effecting [sic]women.” Eleanor Holmes Norton, now chair of the New York City Human Rights Commission, also sent a letter recommending that the women’s representatives no longer meet with management unless accompanied by an attorney. The editors immediately promised that the meetings would be more productive without a lawyer present. We reluctantly agreed, continuing to meet over the summer and into the fall.

One of the major problems in recruiting women writers was that vacancies were not posted. The editors simply continued to recruit through the old-boy network. At one meeting, Oz admitted that the editors didn’t have any “resources” for finding writers; they just asked friends and colleagues in the business, obviously all male. Nor did editors honor their commitment to report what efforts had been made to find a woman when a man had been hired. Asked whether the Nation editor would show the panel some proof that he had searched for a woman in filling a recent opening, Oz simply said no, adding that if a good writer “came down the pike,” he would not want to go searching for a female just to show us they had looked for one.

In July, Lester Bernstein promised to come up with some suggestions for better recruitment but when we met again in September, he said that after talking it over with some of his colleagues, he had thought better of it. At the same meeting, executive editor Bob Christopher said that if Newsweek were forced by law to set up a recruitment program, the editors would simply make up a list of resources and then ignore it. Kermit Lansner, clearly exasperated with the whole process, insisted that Newsweek didn’t need to change its recruitment policies. “Writers come to the magazine over the transom,” he said, “and women aren’t coming. We can’t do anything if they’re not interested.” We told him to go out and look for them. Then, for a good ten minutes, he lamented that actually nobody wanted to come to write for Newsweek anymore. In the end, management never gave us an explanation of what efforts, if any, they had made to find a woman for the last five writing slots filled by men.

We did have some success getting women into the reporting ranks. After a summer internship in Chicago, Lala Coleman became a correspondent in San Francisco in the fall of 1970. Sunde Smith was promoted from Business researcher to reporter in the Atlanta bureau and Mary Alice Kellogg went to the Boston bureau. Ruth Ross, an experienced black reporter who had left Newsweek to start Essence magazine, returned to the New York bureau in 1971. We also got our first female foreign bureau chief when Jane Whitmore, a reporter in Washington, was given that position in Rome in 1971. Management also started hiring men as researchers and finally, after ten years as head researcher in the Foreign department, assistant editor Fay Willey was promoted to associat

e editor.

But there were casualties. When Trish Reilly, one of the most talented young women on staff, was sent to the Atlanta bureau for a summer internship in 1970, the move terrified her. “I was such a depressive, anxiety case,” she recalled. “I was horrified at the thought of being shipped off someplace but I couldn’t say anything because the women were being set free.” The most helpful person was the bureau’s Girl Friday, Eleanor Roeloffs Clift. Eleanor, whose parents ran a deli in Queens, New York, had dropped out of college and gotten a job at Newsweek in 1963 as a secretary to the Nation editor. She was later promoted to researcher and transferred to Atlanta in 1965, when her husband found work there. “Eleanor was the office manager but she ran the bureau,” said Trish. “She gave out the assignments, she did everything, including some reporting.” Indeed, when some of the New York women called Eleanor to say she should stop doing reporting until the editors gave her a raise and a promotion, Eleanor refused and continued her dual roles.

One night Trish was in Birmingham, Alabama, covering a school desegregation story. “I was staying in a crummy Holiday Inn all alone with the Coke machine running outside my door,” she recalled. “I thought, ‘If I have to do this the rest of my life, I will slit my wrist.’ To another woman this would have been a shining moment—covering desegregation in Birmingham! But it totally threatened who I was, being given this adult responsibility, and I was miserable and I couldn’t tell anyone.”

Trish returned to New York after the summer and was offered a permanent spot as a reporter in the Los Angeles bureau. This sent her into a tailspin. “It was announced that I was going to LA and I couldn’t face it,” she remembered. “I told Rod [Gander] I couldn’t go. I knew if you turned down a promotion it was the end of your career, but that was fine. I just wanted to be a researcher.” The only person she confided in was Ray Sokolov, a close friend. Ray told her the editors were bewildered by the fact that Trish had turned down the offer, and they didn’t like it. “Apparently the editors were surprised that a lot of women hadn’t come forward to be reporters and writers,” she later said. “But I understood that because I was one of those women. The women’s movement helped me accept the fact that women were equal to men as intellectuals, but it didn’t change who I was inside. A lot of women were prepared socially and emotionally for it, but for those of us who were traditional women, you couldn’t switch off overnight just because we won a lawsuit.” In fact, Trish thought many of us were too abrasive and too ambitious. “I just didn’t think girls should behave like that—take a man’s job,” she later said. “I found it a little improper.”

Little did she know that some of us “ambitious” types were as conflicted about pushing ourselves forward as she was. I constantly struggled with confidence issues. In 1970, Shew Hagerty, who had promoted me, moved to another department and the new editor was my old boss, Joel Blocker. Since working for Blocker as a secretary in the Paris bureau, I had been writing for nearly a year in New York. But Blocker still saw me as a secretary and told me quite clearly that I would have to prove to him that I could write. Week after week over the next eighteen months, nearly every story I handed in was heavily edited or rewritten. I was so miserable I started looking for another job and thought about leaving journalism. Though I didn’t think the lawsuit was the reason he was punishing me, it didn’t help. I was barely holding on to my job.

By the fall of 1971, a year after the editors committed to “actively seek” women writers, Newsweek had hired three women—Barbara Bright, Susan Braudy, and Ann Scott, a researcher at Fortune—and nine men. Three Newsweek staffers, Pat Lynden, Mary Pleshette, and Barbara Davidson, a Business researcher, had failed their writing tests. The women’s panel was fed up. In October, we reported our frustrations to our colleagues. Furious at management’s intransigence, we once again decided to hire a lawyer. Since Eleanor Holmes Norton could no longer represent us, we were directed to a new clinic on employment rights law at Columbia Law School. One of the teachers was twenty-seven-year-old Harriet Rabb, who agreed to represent us.

Good girls revolt: When Newsweek published a cover on the new women’s movement on March 16, 1970 (above), forty-six staffers announced we were suing the magazine for sex discrimination (seated from left: Pat Lynden, Mary Pleshette, our lawyer, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Lucy Howard. I am standing in the back, to the left of Eleanor Holmes Norton).

The Ring Leaders: When Judy Gingold (top left, in1969) learned that the all-female research department was illegal, she enlisted her friends Margaret Montagno (top right) and Lucy Howard (bottom, with Peter Goldman in 1968) to file a legal complaint.

On the job: Reporter Pat Lynden had written cover stories for other major publications (with writer David Alpern in 1966).

Covering fashion: I was the only woman writer at the time of the suit (with designer Halston and Liza Minnelli in 1972).

The “Hot Book:” Editor-in-chief Osborn Elliott transformed Newsweek in the Sixties. He called the gender divide a “tradition,” but became a convert to our cause (1974).

When Newsweek owner Katharine Graham (with husband, Philip Graham, in 1962) heard about our lawsuit, she asked, “Which side am I supposed to be on?”

The Editors: We called them “the Wallendas” a joking reference to the high-wire circus act (clockwise from top left, in 1969: Oz Elliott, Lester Bernstein, Robert Christopher, and Kermit Lansner).

A key recruit: Fay Willey wanted research—and researchers—to be more valued at Newsweek (1967).

Self doubt: Trish Reilly was afraid to say she didn’t want to be promoted (1970).

Success stories: Religion researcher Merrill McLoughlin (left) went on to co-edit US News & World Report and reporter Phyllis Malamud became Newsweek’s Boston bureau chief (right, with writer Ken Woodward in 1971).

On the move: Elisabeth Coleman was given the first bureau internship in Chicago in the summer of 1970 (below) and became a reporter in San Francisco later that year.

No chance: Mary Pleshette was given one of the first writing tryouts but her pieces just sat on her editor’s desk (1967).

Historic moment: We signed our agreement on August 26, 1970, the fiftieth anniversary of the suffrage amendment (seated clockwise from top left: Eleanor Holmes Norton, Oz Elliott, Kay Graham, Kermit Lansner, Roger Borgeson, Rod Gander, me, Mariana Gosnell, Lucy Howard, Madeleine Edmondson, Fay Willey, Judy Gingold, and Mel Wulf from the ACLU).

Smiles all around: After the signing everyone was hopeful, but the optimism didn’t last long (seated clockwise from left: Mel Wulf, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Oz Elliott, Kay Graham, Kermit Lansner, Roger Borgeson, and me; standing from left: Jeanne Voltz, Lauren Katzowitz, Sylvia Robinson, Harriet Huber, Abby Kuflik, Judy Harvey, Mary Alice Kellogg, Joyce Fenmore, and Lorraine Kisley).

Our Brenda Starr: Reporter Liz Peer was a gifted journalist but the editors wouldn’t send her to Vietnam (1971).

My mentor: Writer Harry Waters said that for women at Newsweek the elevator up “was out-of-order” (1978).

Civil rights: “My attitude was, ‘Go for it,’” said star writer Peter Goldman (1968).

The Famous Writers School: Dick Boeth taught the first writer training program for women with Peter Goldman (1972).

“Female Writer Seligmann”: Jeanie Seligmann was the first researcher to become a writer after the lawsuit (1973).

Victory at last: Our second lawyer, Harriet Rabb, prevailed and later represented the women who sued the Reader’s Digest and the New York Times (1972).

Liberated: Reporter Mariana Gosnell (here in 1967) wrote her first book at age 62.

The Critic: Writer and editor Jack Kroll was brilliant, but recalcitrant (1976).

The boss and me: Looking back, Oz was the first to say, “God, weren’t we awful?” (1975)

Learning the ropes: Media reporter Betsy Carter went on to start New York Woman magazine and write novels (here with striking printers in 1974).

Tough call: Diane Camper was one of the black r

esearchers who decided not to join our suit (1977).

A star is born: Eleanor Clift rose from Girl Friday to Newsweek’s White House correspondent (in 1976, with Vern Smith, left, and Joe Cumming, Jr., in the Atlanta bureau).

The boys’ club: Integrating the story conference (clockwise from left, editor Ed Kosner, Larry Martz, Peter Kilborn, Russ Watson, Dwight Martin, and me, 1977).

Breaking the barrier: My official photo as Newsweek’s first female senior editor, September 1, 1975.

Forty years later: In March 2010, three young women (from left) Sarah Ball, Jesse Ellison, and Jessica Bennett wrote their story in Newsweek—and kept ours alive.

The Good Girls Revolt

The Good Girls Revolt